Clockwise from left: nitrogen helps give stout like Guinness that foamy head (from Wikimedia Commons), nitrogen as it appears on the periodic table, some lovely liquid nitrogen, because gaseous nitrogen has boring photographs (from Flickr).

Nitrogen has the opposite problem to many of the heavier synthetic elements I’ve covered in that there’s a huge amount to talk about. I have picked my favourites, but I just wanted to mention this now because nitrogen is such a big part of Earthly existence and I want to do it justice!

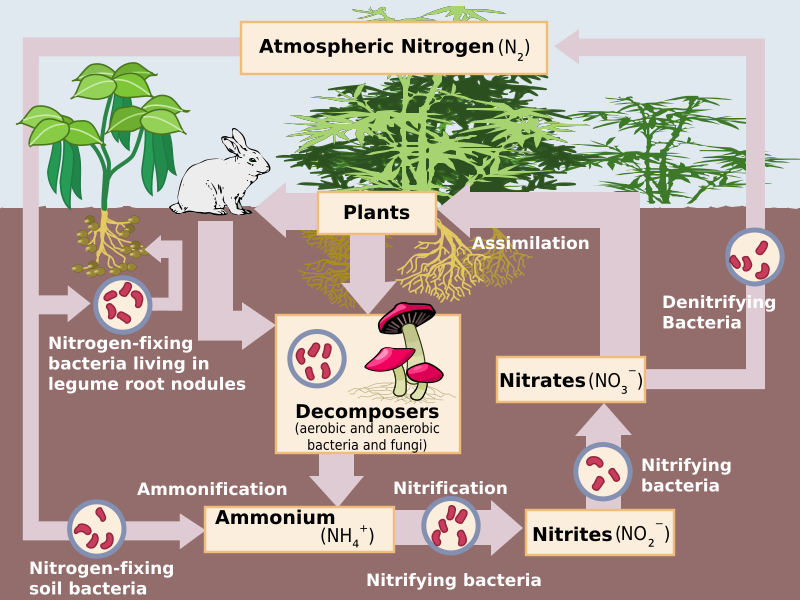

Nitrogen occurs in nature in a multitude of different forms. It is the most common gas in our atmosphere by quite a margin (around 78% of the entire volume) where it exists in its diatomic form, aka two nitrogen atoms bound to each other. Nitrogen is incredibly important to life, as it is used to make essential molecules in biology, including DNA, proteins, metabolites and pigments like chlorophyll. However a lot of life (including us humans) cannot extract nitrogen from the very stable diatomic gas around us, and rely on taking in nitrogen from what we consume. Thankfully there are special bacteria that can “fix” nitrogen from the air into ammonia (NH3) that is released into the soil, where it can be further converted into nitrites (NO2–) and nitrates (NO3–). Nitrates are taken up by plants for use, and then animals can eat the plants (or other animals) to access the nitrogen. To complete what is called the nitrogen cycle, other bacteria can denitrify nitrates to provide energy for themselves and produce nitrogen gas, which goes back into the atmosphere.

Nitrogen can also occur in mineral form, with the most common being nitre, also known as saltpetre (potassium nitrate). Nitre has been referenced since ancient times, and is thought to have meant “ashes from salt” or “washing soda”, which could reference a use of nitre as soap. Other nitrogen compounds, such as nitric acid (called aqua fortis or “strong water” in the middle ages) and ammonium (which was apparently named as it was found in salt form near a temple of Egyptian deity Jupiter Amun), have also been known well before it was thought that nitrogen was its own element.

The official “discoverer” of nitrogen was Scotsman Daniel Rutherford in 1772. Despite not concluding it as a new element, he did isolate it from a sealed quantity of air by using a candle to remove the oxygen and a scrubber to remove carbon dioxide. What was left did not allow for combustion, and a mouse could not survive in it, leading Rutherford to label this substance “noxious air”. Other scientists working on it included Carl Scheele, Henry Cavendish, Joseph Priestly and Antoine Lavoisier, and other names like phlogisticated air, mephitic (another term for noxious) air and azote (Ancient Greek for “no life”) were floated around. We’ll cover phlogistication later with oxygen. However once French chemist Jean-Antoine Chaptal realised that this noxious air was a key part of nitric acid and therefore nitre, he proposed the name nitrogen, combining nitre with the French “gène” meaning producing (which in turn comes from Ancient Greek for “begotten”). Some compounds still use the old terminology though, such as hydrazine (N2H4) and azide ions (N3–).

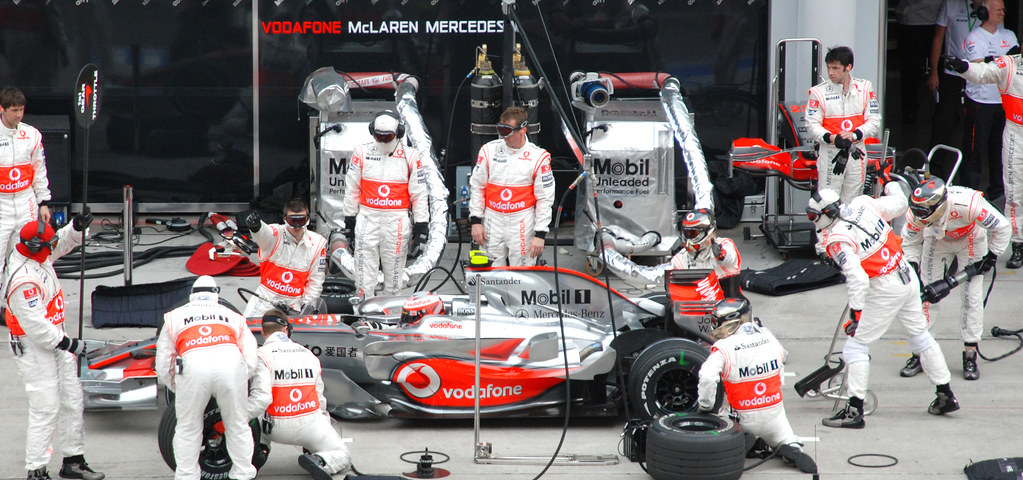

Nitrogen’s relative inertness has led to some interesting applications. It is used in food packaging (sometimes in combination with carbon dioxide) to preserve the food inside by depriving any life on it of oxygen, as well as preventing oxygen from reacting with the food. So when you open your bag of crisps, that’s not air inside- that’s just nitrogen! Nitrogen added to food is also an E number (E941). Nitrogen is used to create inert atmospheres inside light bulbs, as well as in racing car and aircraft tyres. The oxygen and water vapour in air will not expand and contract consistently with the weather, leading to handling and traction difficulties. But nitrogen is way more consistent, and therefore is used instead. In case you were worried that your normal car was deprived, nitrogen gas is usually what fills car airbags, using the rapid decomposition of sodium azide.

Nitrogen is also used sometimes when making beer, particularly ales and stouts. Nitrogen, or a combination of nitrogen and carbon dioxide, can be used to pressurise beer kegs as it produces smaller bubbles, leading to a smoother and “headier” beer (I’ve been told headier is the correct term). In fact, those weird balls (called widgets) that started appearing in Guinness cans contain nitrogen gas, so that when you open your can of stout you get the same thick foamy effect as if it was just poured from the tap.

A very famous use of nitrogen in the laboratory, on YouTube and at weird science themed cocktail bars is in its extremely cold (-196°C) liquid form. Liquid nitrogen is so cold that it can be used to preserve cells in a laboratory by immediately freezing them to stop enzymes or other chemical reactions that might damage them (cryopreservation). It also freezes cells in a way that doesn’t form ice crystals, which would rupture them and destroy them anyway. In this way scientists can store bacteria, sperm, eggs and other biological material in such a way that they can carefully thaw the cells out for future use. But before anyone gets any ideas, current technology does not allow cryopreservation of entire humans, as it still does too much damage to the body and brain as a whole. Sorry! One good thing is this freezing without causing ice crystals to form allows people to make incredibly smooth ice cream with liquid nitrogen, so there’s that.

And that’s nitrogen- a very cool, cyclic and foul-smelling (apparently) element!

2 thoughts on “Day 40: Nitrogen”