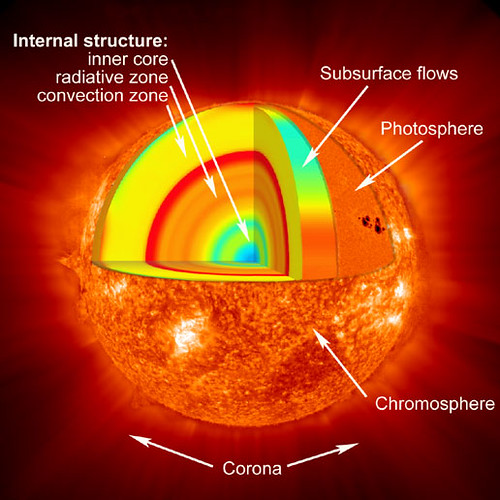

Clockwise from left: the obligatory helium balloon photo (from Pxhere), the less obligatory MRI machine (from Wikimedia Commons), helium as it appears on the periodic table.

Helium is a rather special element, having been the first to be discovered off the Earth before it was found on the Earth.

In the mid-19th century, a French astronomer called Jules Janssen was studying the chromosphere, a red-coloured layer of the sun that can only usually be seen during an eclipse. Whilst looking at the chromosphere through a spectroscope, Janssen found an incredibly strong line in the yellow part of the visible light spectrum. A line of this specific wavelength had never been seen before, and when English astronomer Norman Lockyer saw it too when observing the sun’s spectrum, he concluded it to be due to a new element. He named it helium, using the Ancient Greek word “helios”, meaning “sun”. Later in the 19th century helium was detected on Earth, with physicist Luigi Palmieri finding it splurting from Mount Vesuvius, and chemist Sir William Ramsay isolating helium from a mineral called cleveite by exposing it to acids. The atomic number was not determined until 1895 by Swedes Per Teodor Cleve and Abraham Langlet.

Helium is an exceptionally light element, with only hydrogen being lighter. Helium is also a noble gas, the group of elements found in the column at the far left of the periodic table. As the trend is that the outer electron shell of the atom fills up as you move left across the table, the noble gases are notable because their electron shells are full- to add any more electrons would require a tonne of energy to create a new shell. Interestingly it would also take a tonne of energy to take one electron from the atom too, as a full shell is incredibly stable. The upshot of all this is that the noble gases are incredibly unreactive!

This is why as well as being used for floating balloons (as helium is much lighter than nitrogen, oxygen and all the other gases in the air bar hydrogen), helium is what is used to let airships like blimps float along. This is much safer than hydrogen, which despite being lighter is a lot more reactive and therefore dangerous to have in massive quantities above your head thousands of feet in the air.

The largest application of helium, however, is nothing to do with floating balloons. It is in fact the use of liquid helium as a cryogenic substance. Liquid helium is around -269°C, and is used to cool superconducting magnets, like the ones found in MRI scanners. This is because superconductors have a strange property that below a certain temperature, their electrical conductivity goes through the roof! This high level of conductivity is needed to create the powerful magnetic field needed for MRI.

I couldn’t finish talking about helium without describing its effect on the human voice. It is a misconception that breathing helium makes your voice higher- in fact, it just changes the timbre (the sound itself) through increasing the natural resonance frequency of your vocal tract. It does this because the speed of sound is much faster through helium, stretching out the sound waves such that lower-sounding wavelengths no longer vibrates your vocal chords, but higher sounding wavelengths are stretched just right to be amplified out. Overall this makes your voice sound like a strange duck without necessarily changing the pitch!

And that’s helium: the squeaky, tiddly inert element!