Clockwise from left: LEDs contain indium (from Wikimedia Commons), indium as it appears on the periodic table, a fancy ingot of indium (from Wikimedia Commons).

Here we have another element (vicariously) named after a country: indium! It is a relatively soft metal with mainly electronic applications, as you’ll see later.

But first, indium was discovered in the best century for discovering elements- the 19th. This time it was a chemist duo of Ferdinand Reich and Hieronymous Theodor Richter who found indium whilst analysing minerals they were extracting in Saxony. They were using a classic root of names for elements, the spectroscope, in these analyses, when they found an unexpected blue line emerge in the spectrum of colours produced. This led to the duo deducing that a new element must exist in the minerals, which they named indium after the indigo line that formed. “But wait”, I hear you cry, “didn’t you say this was named after a country?” Yes, but only through the fact that the colour indigo was named after the dye, which in turn was exported from the country of India (in fact, the word is Latin for “from India”). So I think it counts.

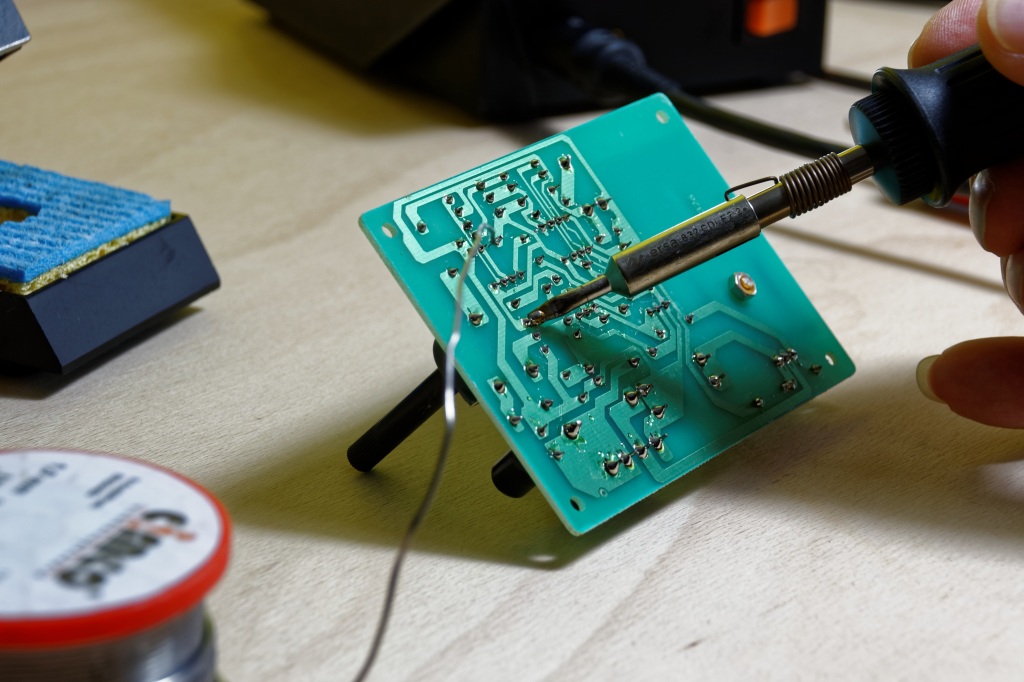

The first real use of indium was for alloying with metals to stabilise them. This was used to protect bearings of world war II aeroplanes against corrosion. But more modern uses are predominantly, as promised, in electronics. Its softness and conductivity mean it is used in solders and as a semiconductor when combined with other elements, which are used in solar panels and LED lights.

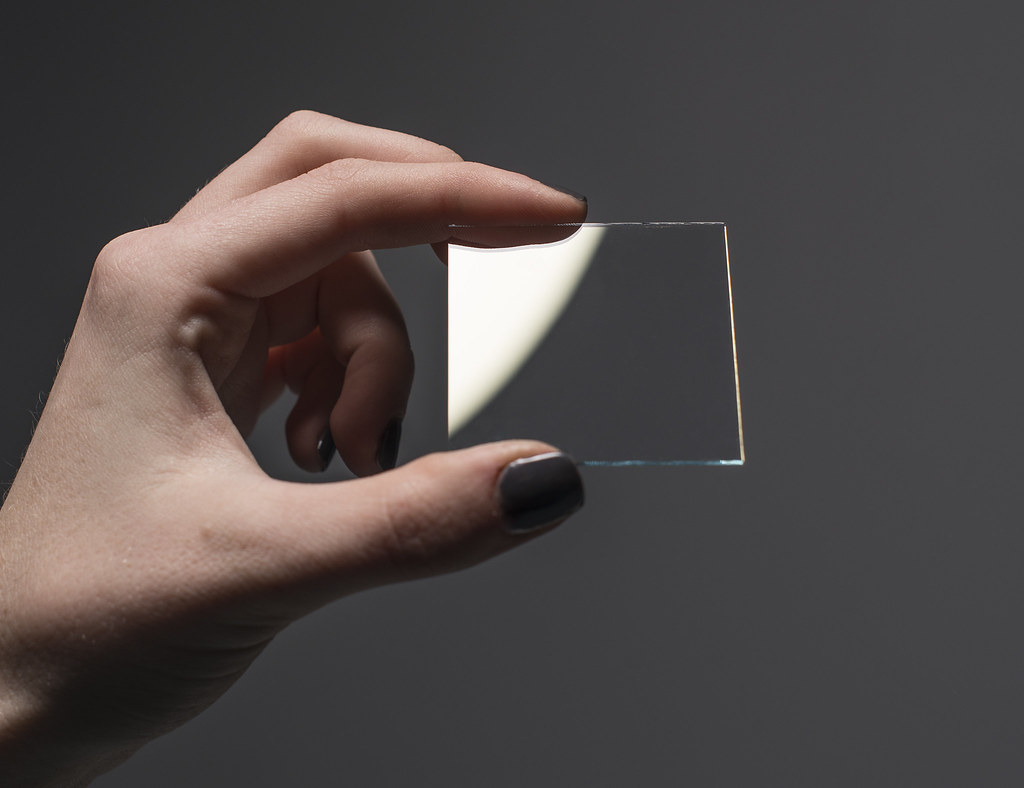

Possibly the most interesting conductive material using indium is indium tin oxide (ITO). This chemical is both highly conductive to electricity but also transparent, and can function in incredibly thin layers. This means that ITO is incredibly useful as an electrode in liquid crystal displays (LCDs) in flat screen televisions and smartphones. The electronic field created in the screen of the smartphone using ITO as the conductor can be disrupted by interacting with another electrical conductor, the human body, which is then detected by the phone. This is how capacitive touchscreens work. Other more niche uses of ITO include in aircraft windshields and supermarket freezer doors, as the voltage passed through helps defrost the glass. Solar panels are also a common use of ITOs. Turns out there are a lot of uses for something conductive and transparent!

Left: ITO layered on some glass, can you spot it? From Flickr. Right: a touchscreen smartphone. From Pikrepo.

So that’s indium: a soft, conductive element of the rainbow!

2 thoughts on “Day 46: Indium”