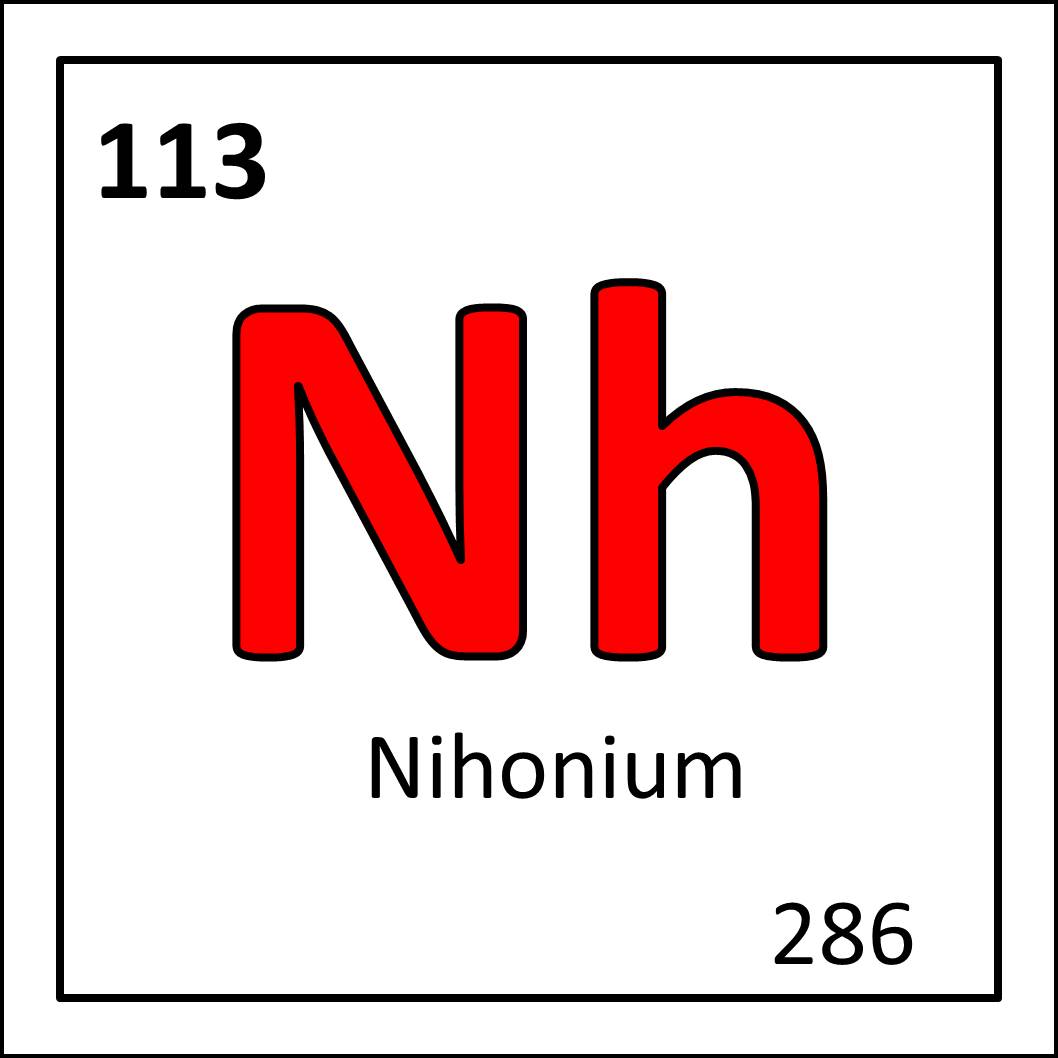

Left: nihonium as it appears on the periodic table. Right: the Riken research institute in Wako, Japan, who have credit for discovery of nihonium (from Wikimedia Commons).

You always know when an element is relatively new because when you write it in a blog post the little red underline of an unrecognised word appears beneath. This is certainly the case for nihonium, a synthetic element first created in the 21st century. As another element that is pretty unstable (the most stable form has a half life of 10 seconds), there are no real applications of nihonium, but there is an origin story that I’ll cover now.

Two institutions have laid claim to the discovery (or rather, synthesis of element 113): the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Moscow and the Riken Institute in Japan. The JINR team consisted of both Russians and Americans, who in 2004 published an observation of element 113 after bombarding americium with calcium. This fusion reaction resulted in element 115 (moscovium), which then decayed, giving of an alpha particle (two protons and two neutrons) from its nucleus to make element 113. Around the same time, a group led by Kōsuke Morita at Riken had been bombarding bismuth with zinc in an attempt to make element 113, which was successful in the summer 2004 when a lone atom was detected.

So who discovered it first? Well according to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP), a new element is only truly discovered when the element is proved to have a novel atomic number, the experiment to isolate/create it must be repeatable by other research groups, and its properties must be established and unique. Now despite JINR having performed the experiments and creating element 113 first, IUPAC and IUPAP said in 2015 that the Riken group’s method was confirmed faster, and therefore they have claim to discovery and naming. This was because the way teams confirm the synthesis of a new element is through analysing the decay chain, which is the series of elements created whilst the element decays. The Riken group’s synthesised element 113 followed a decay chain that was already firmly established, whereas the JINR decay chain was less well known and required further research to confirm. As much as JINR were not happy with this decision, they did get claim over elements 115, 117 and 118, which they were also working on at the same time.

The Japanese team at Riken were overjoyed at this decision, and wanted to use the naming rights to promote the Japanese contribution to science. A few names were thrown about, including rikenium, japonium and nishinanium after eminent Japanese physicist Yoshio Nishina. In the end they wanted the element to be named after the Japanese pronunciation of Japan, of which there were two: Nippon and Nihon. “Nipponium” had been put forward before unsuccessfully by Masataka Ogawa in 1908 for rhenium, and Np was taken by neptunium, so the name nihonium was used instead.

So that’s nihonium, an element that was given its name within the last 5 years!