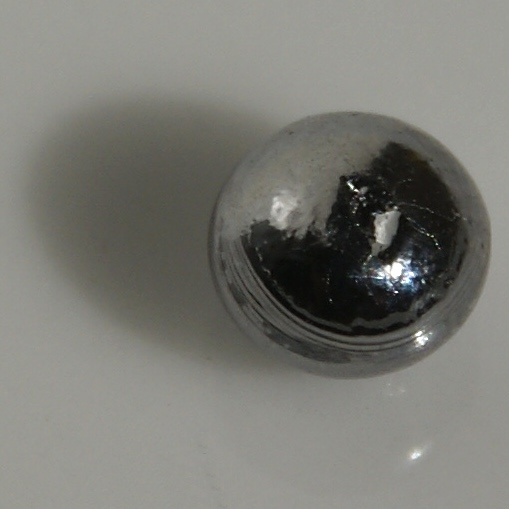

Clockwise from left: a fancy ball of rhenium (from Wikimedia Commons), tasty pizzas rely on rhenium alloys in oven filaments heating up (from PxFuel), rhenium as it appears in the periodic table.

Rhenium is an element that many may not have heard of, but has quite an interesting past and some useful modern applications. Although it is named after a region of Germany, if history had played out differently could have been named after the entire of Japan…

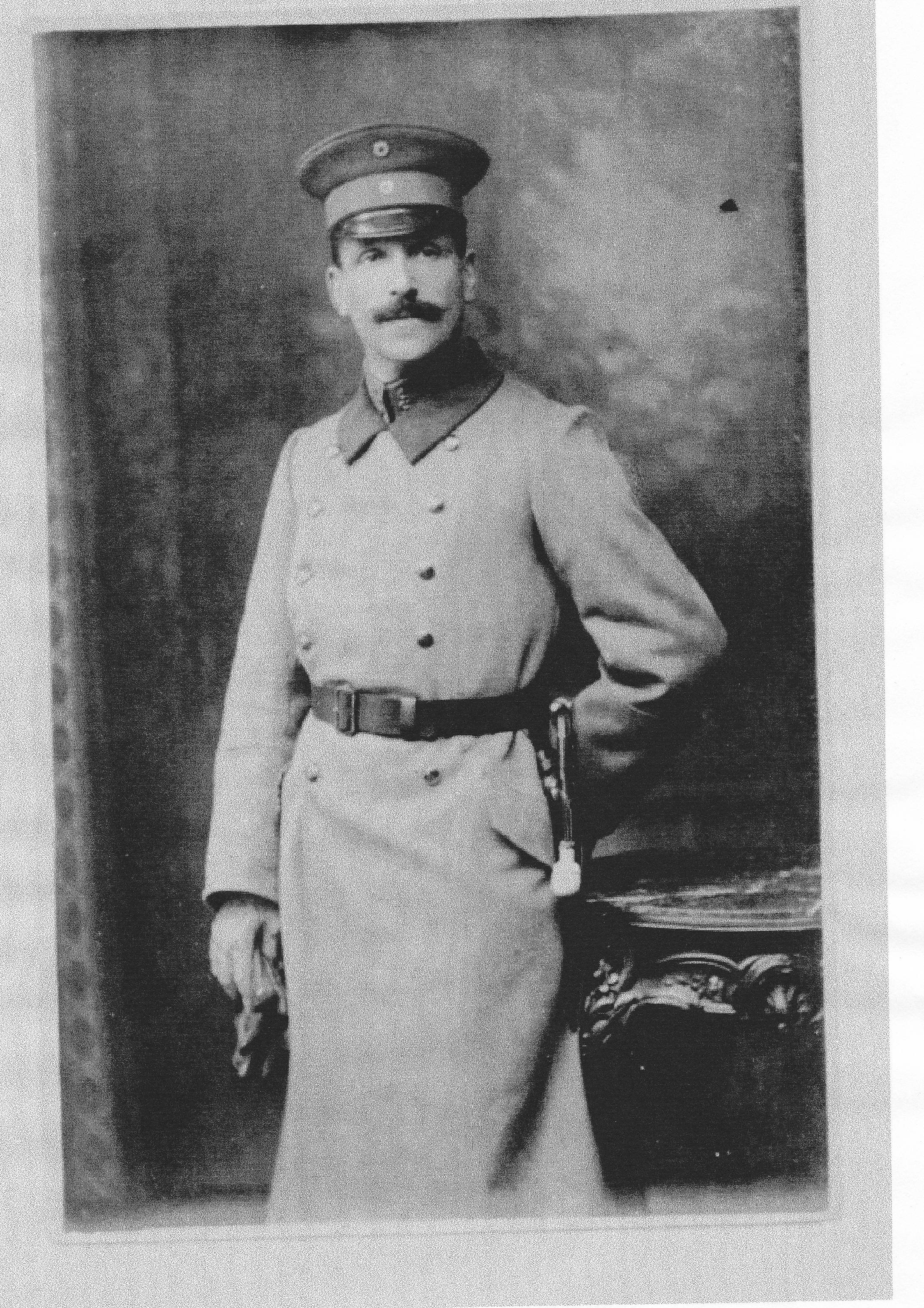

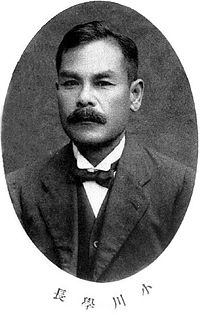

The official discovery of rhenium is credited German chemists Otto Berg and the Noddacks (Walter and Ida) in 1925. They found element 75 in platinum ore and in the minerals columbite, gadolinite and molybdenite. They named the element after the Latin for the Rhine area of Germany, Rhenus. But the story doesn’t stop there, because over a decade before the Germans the Japanese chemist Masataka Ogawa is thought to have discovered element 75 first. At the time Ogawa thought he had discovered the 43rd element, but no one could replicate his experiments, and so Ogawa’s discovery was gone from people’s minds. Looking back many now think he had found rhenium, and his intention was to name this new element “nipponium” after his home country of Nippon (or as it is known in English, “Japan”). The other term for Japan, Nihon, was eventually used for element 113 in Ogawa’s honour.

(From left to right): Otto Berg (from Wikimedia Commons), Ida Noddacks (from Done via Wikimedia Commons), Walter Noddacks (from alchetron.com) and Masataka Ogawa (from Wikimedia Commons), the founders of rhenium.

Rhenium is an exceptionally rare element on Earth. In fact, Berg and the Noddacks only managed to get 1 gram of the stuff from 660kg of molybdenite. Even nowadays the commercial production of rhenium comes from flue dust extraction from molybdenum smelters. So the uses for rhenium have been quite limited.

However, one of the main uses for rhenium is in alloys. Rhenium has a very high melting temperature, a high creep strength (meaning it is resistant to warping or deforming when subjected to persistent long term force) and is quite resistant to vibrations. This has allowed for alloys with nickel and tungsten to make oven filaments and thermocouplers (which can measure temperatures above 2000°C), and superalloys that are used in jet engines. Tungsten is the only metal with a higher melting point than rhenium, meaning that the addition of rhenium actually allows the alloy to be more malleable and shape-able! Tungsten-rhenium alloys are also often used in x-ray machines due to its robustness.

The other main use of rhenium is as a catalyst, for example in petroleum refining. This means it can lower the energy needed to start a chemical reaction, and has the added bonus that the catalyst itself isn’t used up in the process. One thing that can happen to catalysts though is an unwanted reaction with a chemical present in the reaction chamber which causes the catalyst not to work as well any more (known as catalyst poisoning). Rhenium is pretty resistant to common poisoners nitrogen, sulphur and phosphorus, meaning that rhenium catalysts can be used in reactions where these kinds of poisoning is common, such as hydrogenation reactions (adding hydrogen to chemicals).

And that’s rhenium- a Japanese German, poison-resistant, rare metal element!

One thought on “Day 72: Rhenium”