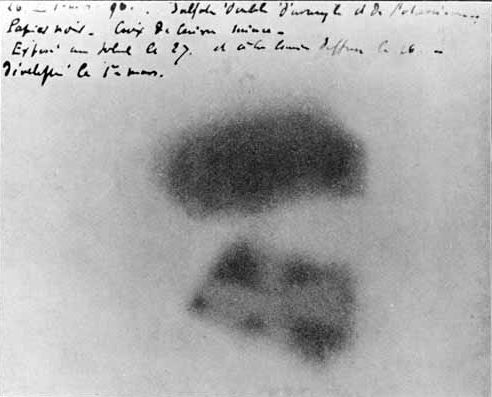

Clockwise from left: a very exciting picture of Uranus (from Pixabay), a lovely dangerous disc of enriched uranium (from Pixabay), uranium as it appears in the periodic table.

Well here we are: the posterchild of radioactive elements: uranium! This is a tricky post to write highlighting the importance of this element considering how much we’ve discussed radioactivity already, but uranium has the unique aspect of being the reason why we know about radioactivity, and nuclear physics owes a lot of its 21st century discoveries to it.

Uranium can be found in nature, and is the heaviest of what are called the primordial elements. Primordial means “existing at or from the beginning of time”, so effectively what we mean here is that uranium was believed to be the heaviest element that has existed since Earth and the Universe formed. This distinction is needed because the slightly heavier element plutonium has since formed in miniscule amounts in uranium ores due to uranium atoms capturing radiation, and therefore is the heaviest element found currently in nature.

Me being pedantic aside, uranium has rather surprisingly been in use since the first century BC. Uranium oxide was used by the Romans to create a yellow glaze for their ceramics. Since then uranium appears in history as the mineral pitchblende (a form of uraninite), which in the middle ages was used to colour glass. It was this pitchblende that was what German Martin Heinrich Klaproth dissolved in nitric acid and then neutralised with sodium hydroxide to produce a yellow powder in 1789. Klaproth determined that this powder was an oxide of a new element, and subsequently named it after the recently discovered planet Uranus.

The history of uranium then continues to the 19th century, where French physicist Henri Becquerel was working with the element and left a sample on a photographic plate. This previously clean plate that had been kept in a dark drawer suddenly had been fogged up as if it had been exposed. This led Becquerel to suggest that the uranium had given of some invisible rays, and thus radioactivity had been found.

Of course, after Meitner, Frisch and Hahn’s discovery of nuclear fission in the late 1930s uranium started getting a new reputation. Therefore the most famous uses of uranium are in nuclear power stations, submarines and nuclear weaponry, where the high capability for uranium-235 to undergo fission leads to a very high energy-releasing chain reaction when the nucleus splits. This isotope of uranium is actually quite rare compared to the not-so-fissionable uranium-238, often leading to enrichment of uranium-235 being needed for nuclear reactions to occur. Uranium also has been used very often as the element that is bombarded with other atoms or nuclei to synthesise heavier elements, as seen in many of the posts here.

These haven’t been the only uses of uranium in the past century. With the popularity of radium use in glow-in-the-dark paints, uranium was starting to become a waste product in radium extraction. The biggest outlet for the uranium was therefore in glazes for pottery and tiles for kitchens and bathrooms. Uranium salts come in all sorts of colours, which lended itself well to glazes. These salts were also used to colour silk and wool, and there was even a time when uranium was used in porcelain dentures, which didn’t stop properly until the 1980s! This was because the uranium would fluoresce under light, creating a more gleaming and apparently “natural” look. Uranium glass, a popular tableware product in the 20th century, also fluoresces rather brilliantly under UV light, giving that characteristic greeny colour we associate with radioactivity.

And that’s uranium: the classic, original radioactive element!

3 thoughts on “Day 85: Uranium”