Clockwise from left: a very blurry photo of Enrico Fermi (from Wikimedia Commons), an alloy of fermium and ytterbium containing 0.00004% fermium used to determine some of the characteristics of fermium (from By Ben E. Lewis through Wikimedia Commons), fermium as it appears on the periodic table.

We haven’t quite reached 100 posts, but we have reached the 100th element: fermium! At this point you know the drill: it’s a synthetic heavy element named after a famous scientist and with no applications outside research. The most stable isotope of fermium out there has a half-life of 100.5 days, so researchers have a little more time to work on it than some of the superheavy elements.

The discovery of fermium is a little more unique than a lot of the other transuranic elements. Like einsteinium, element 100 was found after the Ivy Mike nuclear test in 1952, but unlike einsteinium, this element was going to be a lot rarer as it is a larger atom. So after einsteinium was found and the concept of these new elements being created was formed in scientists’ minds, coral from the test site at the Enewetak atoll were analysed in Berkeley, US. From this element 100 was separated, but because of the Cold War being in full swing at the time this discovery was kept a secret. Instead the team at Berkeley, headed by Albert Ghiorso, managed to make element 100 by bombarding plutonium with neutrons. This data was published in 1954, a year before the Ivy Mike business was declassified.

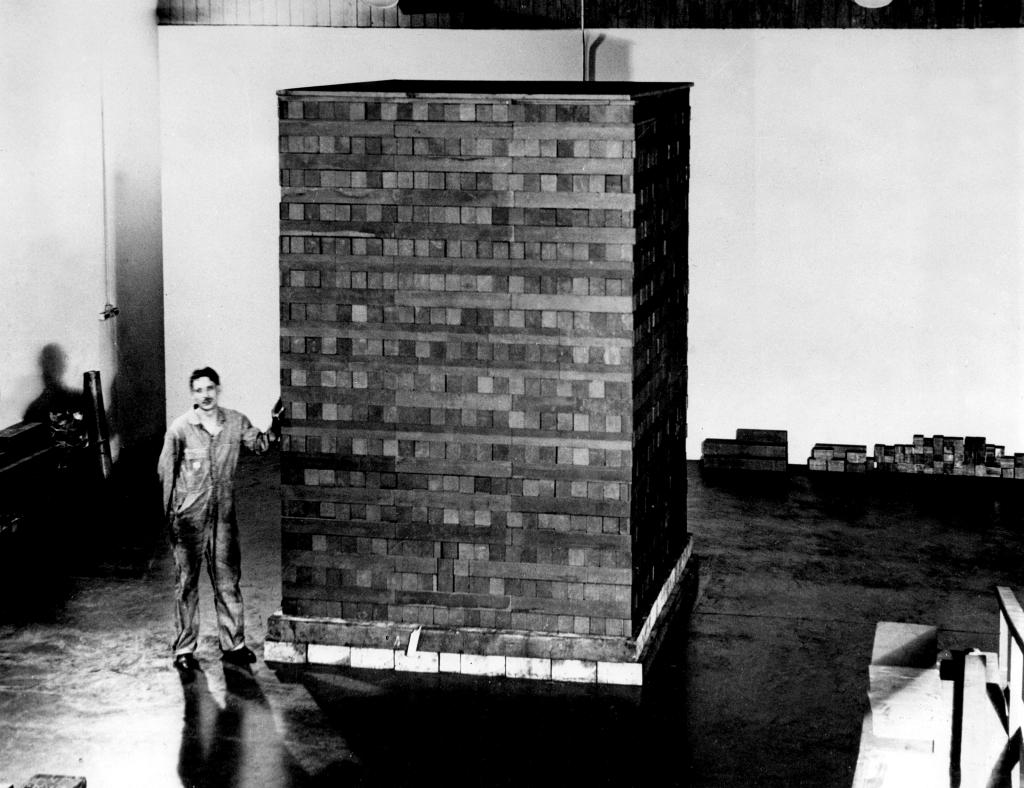

The element was named after Enrico Fermi, an Italian physicist and “architect of the atomic bomb”. So I guess it fits that an element first created by a nuclear weapon was named after him, even though after the first hydrogen bomb tests Fermi strongly opposed further development of these explosives. His work on using neutron bombardment to create radioactive substances earned him the Nobel prize in 1938, but it was after he had fled to the United States with his Jewish wife to escape Italian anti-Semitic racial law that his architecture status comes in. He became part of the Manhattan Project, and developed the first every artificial nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1. The reactor used uranium fission from neutron absorption to start a chain reaction whereby the neutrons released of one atom splitting whack into another atom and causes that to split too. For a nuclear reactor to work, what is called criticality needs to be achieved- effectively when the rate of neutrons being produced in the reaction is larger than the neutrons being lost due to leakage or otherwise. When criticality is reached neutrons no longer need to be fired into the reactor, and it becomes self-sustaining. Chicago Pile-1 reached this state in 1942, and from that the nuclear reactor was born.

And that’s fermium: a coral-destroying, critical and Italian element!