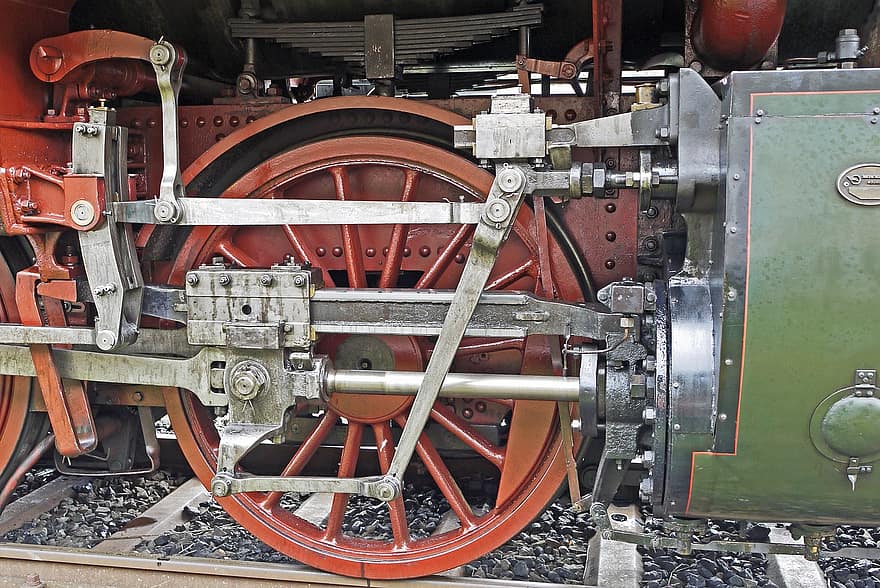

Clockwise from left: some shards of vanadium (from Wikimedia Commons), vanadium as it appears on the periodic table, piston rods often use vanadium steel due to its toughness (from Pikist).

I always like to find the most tenuous connections between element etymology, so for vanadium I will say that in a way it was named after the same Goddess as Friday. Bit of a stretch when you see how below but I’m sticking by it!

Vanadium is a transition metal, so once again we can expect some colourful oxidation states. The oxidation states that vanadium most commonly achieve (and their colours) are +2 (purple), +3 (green), +4 (blue) and +5 (yellow). This means vanadium is very happy to lose either 2, 3, 4 or 5 electrons from its atoms, and the electron configurations given in these ions result in the absorption of specific wavelengths on the visible spectrum, giving nice bright colours!

Vanadium was an element that was discovered twice. The first time was at the start of the 19th century when Spanish mineralogist Andrés Manuel del Río extracted the element in Mexico from what is now called vanadinite, but was then called “brown lead“. Del Rio initially named the element panchromium because of all the colours that the element’s salts could form (pan=”all”, chroma=”colour”), and later erythronium (from the Greek erythro, meaning “red”) because these salts turned red when heated up. Unfortunately when French chemist Hippolyte Victor Collet-Descotils analysed a sample he convinced Del Rio that it was chromium with impurities, and so Del Rio retracted his claim.

This false retraction meant that vanadium stayed a secret for 30 more years, after which Swedish chemist Nils Gabriel Sefström found vanadium in some iron ores in Stockholm. Sefström decided to go with vanadium for the element’s named after the Norse Goddess of beauty, love and fertility Vanadís, who also goes by the name Freyja (which is where we get Friday from). Apparently this choice was because Sefström noticed there wasn’t an element beginning with the letter “V”, which is a little strange but fair enough. German Chemist Friedrich Wöhler also confirmed del Río’s findings in 1831, so Andrés did get some closure on his work even if his element names did not go through in the end.

Vanadium’s colourful oxidation states can sometimes be used in coloured ceramics and glass, but the main use of vanadium metal is in alloying with iron and steel. Vanadium steel is very strong, and shock and vibration resistant, meaning it is often used in axles, piston rods, crankshafts and armour plating. Vanadium steel with increased carbon also gets use in surgical instruments and various tools for its incredible robustness. Also combining vanadium with titanium and aluminium provides a very tough heat-resistant alloy used in jet engines.

Vanadium has also been found to be used in various enzymes, and seems to be very important to sea life. Many marine algae have an enzyme called vanadium bromoperoxidase, an enzyme that helps remove dangerous levels of hydrogen peroxide that can be produced during photosynthesis. Strange little sea invertebrates called ascidians and tunicates actually store vanadium in specialised blood cells called vanadocytes, although the current reason for this is unknown. Some experts have suggested that it is used to deter predators. Some soil-based bacteria also use vanadium in nitrogenases- enzymes that “fix nitrogen“, which means they convert atmospheric nitrogen into nitrogen chemicals usable by nature, like ammonia. Vanadium may even be essential in human diets, but this has not been 100% confirmed yet.

And that’s vanadium- the colourful, lovely and saline element!

One thought on “Day 103: Vanadium”